The goal

Generative Adversarial Networks, or GANs for short, are a pretty neat type of neural network. Train them on a large enough set of data points belonging to the same distribution, and they’ll be able to generate new data points sampled from that distribution. In other words, give them a lot of examples of something, and they’ll be able to generate new and never-seen-before instances of that thing, according to their own understanding of the original dataset.

They’re pretty well-known by now, and people have been applying them to pretty much any dataset they could get their hands on : pictures of faces, music, Pokemons, anime girls…it’s always fun and frankly fascinating to see an artificial intelligence create something on its own, even if it’s under the supervision of human beings.

I decided to try out GANs as well, and what better way to start the journey than unleashing their power on one of my favorite shows : Gundam !

Gundam is a sci-fi franchise hugely popular in Japan, spanning across a bajillion of anime series, mangas, novels, and games. It features giant bipedal robots called “mobile suits”, which, in the story, are generally piloted from the inside by a human being (think of them as walking tanks). Mobile suits are at the heart of the Gundam franchise, and each new series introduces its own unique designs and variations. Given that the franchise is celebrating its 40th anniversary this year, there are literally hundreds of different designs scattered across the Gundam multiverse.

To me, mobile suit designs are a large part of what make Gundam so interesting. Besides the coolness factor of “giant robots with over-powered abilities”, they are often incredibly detailed, and have their own style and quirks that match the universe/time period they evolve in, as well as the faction they belong to within the story.

So, what would happen if we shoved images of all those designs into a GAN ? Could we teach a neural network to come up with its own designs ? That’s the GANdam project ! (I won’t apologize for the awful pun name, it was so obvious I couldn’t not do it).

The data

Very often, obtaining the dataset to train a neural network is half the battle. I honestly thought this first step was already going to be a show-stopper, as I didn’t have the time and patience to watch and rewatch all Gundam series and manually crop out the mobile suits when they show up on screen.

Fortunately, there are in this world even bigger mecha nerds than me, and some of them have been maintaining very exhaustive online databases, referencing all mobile suits models even from the most obscure series withing the Gundam franchise.

My original plan was to scrape up The Gundam Wiki for pictures of mobile suits. That website is extremely exhaustive and definitely a reference for anything Gundam-related, but unfortunately it’s also using some kind of generic wiki framework that makes its HTML very messy and hard to scrape with a simple script.

But then I struck gold with [mahq.net](https://www.mahq.net/mecha/gundam/index.htm. Not only that website has all mobile suits neatly sorted by show and their dedicated pages arranged in a simple and consistent HTML, but their illustration pictures show them in a consistent pose, with the same background color, and (generally) in a 400x400 square image. I couldn’t believe my luck.

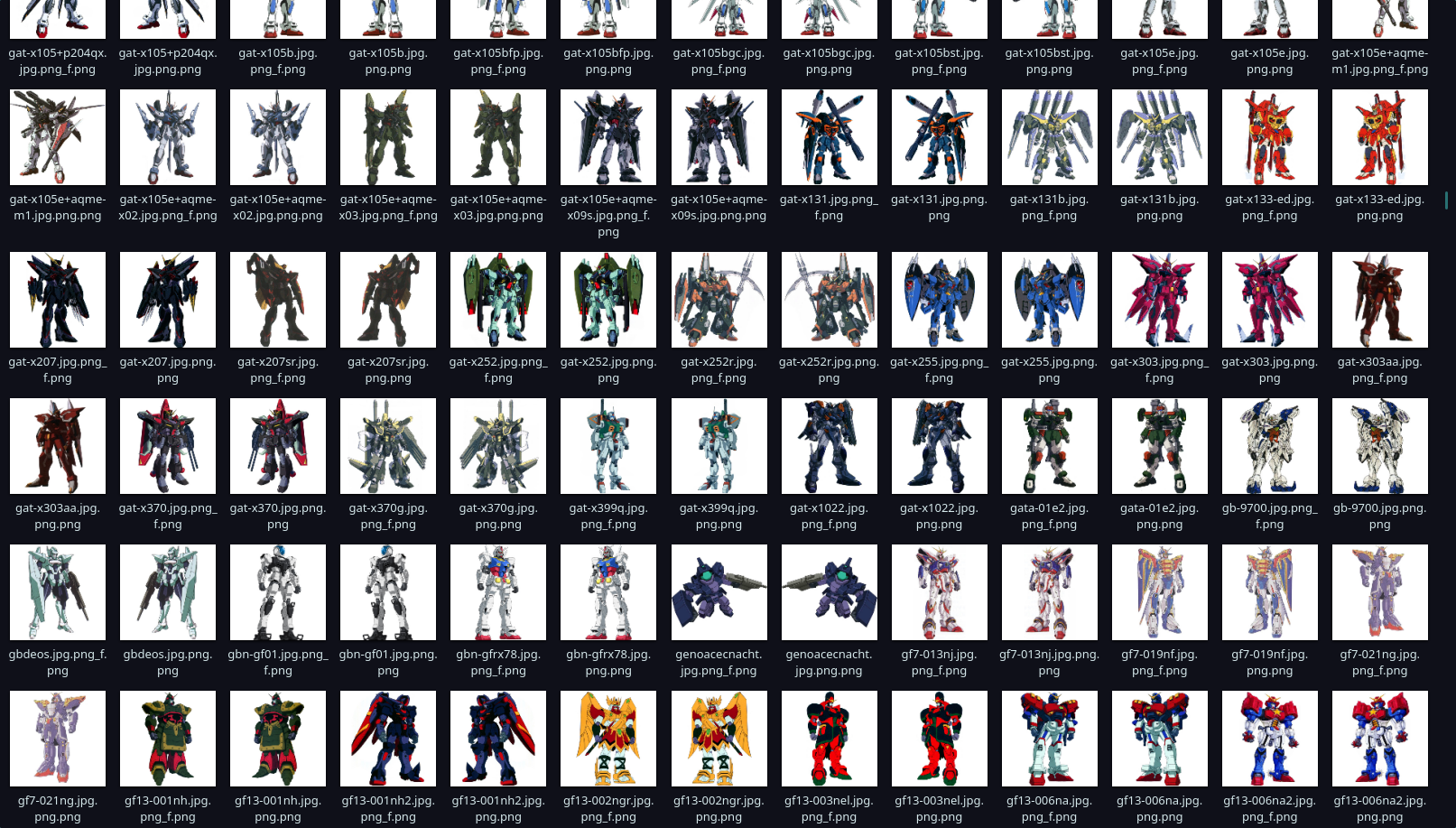

I used Python and BeautifulSoup to build the scraping script. This was my first attempt at web scraping, but fortunately that module makes browsing a website DOM extremely easy. Getting the script to download only mobile suit pictures was another story, though. Mobiles suits aren’t the only machines in the Gundam universe that are referenced by mahq.net, and so my scraped dataset would often get polluted with pictures of planes, boats, spaceships, and even a goddamn truck trailer. Detecting the words “mobile suit” in the page helped a lot to sort it out, but I still ended up with false positives that had to be manually removed. Also, some mobile suits were identified as “transformable mobile armors” because of their special capabilities, so I had to take care of that. Oh, and also, for some reason, the series “G Gundam” names its mobile suits “mobile fighters”, so I had to change the filter.

Once the scraping and manual sorting was done, I ended up with a dataset of exactly 1666 images. Yep, every single one of them is a unique design. The Gundam franchise is absurdly huge. And that was after removing some unconventional ones, like the Zeong. I wanted to focus on bipedal shapes to limit the variance, so that the GAN would not get confused too much during training. I also removed the (rare) images that didn’t have a gray background, were in black in white, or were photographs of plastic models.

At some point, I also realized that some images had the mobile suits facing to the left, and other to the right. Not having the patience to flip them all to the same side, and being short on data points (1666 images may sound like a lot, but it’s really tiny in machine learning territory), I decided to augment the dataset by including a flipped copy of every images. Which totaled to 1666x2 = 3332 images. The GAN would maybe get confused not knowing which direction to point its generated models, but for a first result I didn’t think it would matter too much.

Finally, all images where resized to a 128x128 format (with padding when necessary). The resolution of the original dataset was enough to go with larger images, but for a first attempt I wanted to keep the computational cost low, as the dimensions of the input images directly impact the memory consumption of the model. 128x128 kept the memory cost low without sacrificing too much on the details.

The architecture

GANs are a hot research topic these days, and so the state-of-the art is constantly changing with new architectures and clever tricks. I didn’t really know what to start with, but the article Must-Read Papers on GANs by Connor Shorten provided a good crash course that pointed me in the right direction. I followed the author’s advice and decided to implement the DCGAN architecture, because it’s simple enough and probably a good starting point for future improvements.

I looked for a reference implementation in Keras (which I’m most familiar with) and found another gold mine : Keras-GAN, a GitHub repository containing not only an implementation of DCGAN, but also a good two dozens of other GAN architectures. With that resource in hand, my job was going to be pretty easy.

DCGAN only uses standard layers included in Keras, so building the architecture itself would have been trivial even without that reference implementation. However, to train a GAN you have to share some layers between two neural networks (the discriminator network and the combined generator+discriminator network) and regularly freeze and unfreeze their weights depending on which one of them you are currently training. Keras does not expose those features in a very obvious manner (and even rains you down with warnings if you try to use them in its current version), so being able to mimic an existing, working implementation was a huge time-saver (and I definitely learned a lot about Keras along the way).

I didn’t make a lot of changes to the DCGAN architecture, besides tweaking the number of parameters and the network depth in my attempts to stabilize the training. I followed the suggestions of the original paper and used ReLU as the activation for the generator layers, Leaky ReLU for the discriminator, and applied batch normalization to the inner layers of both.

The training

GANs are notoriously hard to train. Traditional neural networks generally have a single training loss, and you watch it go down as the training progresses. Ideally, you also compute that loss on a validation dataset to know when it’s time to stop the training and prevent overfitting. GANs have two losses, one for the generator and one for the discriminator, and you don’t want either of them to reach zero. If one of them do, it means that the generator has over-powered the discriminator or vice-versa, and your training gets stuck in a state where it’s difficult to recover from. Ideally, you’d want to maintain a balance between the two models, so that they learn at the same rate and get in a positive feedback loop where an improvement on one side forces the other to improve too.

I’ve found there are a few knobs you can act on if the training goes too much in favor in one or the other :

Learning rates : you can have different learning rates for the generator and the discriminator, and decrease/increase them depending on which direction you need the balance to go.

Model complexity : you can reduce and increase the number of parameters in either model, or even their depth. My intuition is that you should not prune either model too much, though. If your models don’t have enough parameters to grasp the complexity of the latent space, it will probably makes the generated end result less realistic.

Labels noise : for the discriminator training, instead of labeling all generated images as

0and the fake ones as1, you can label them asalphaand1 - alpha, wherealphais a random variable sampled between 0 andalpha_max. By increasing or decreasingalpha_max, you can introduce more or less noise in the discriminator labels, effectively “blurring” its vision of the latent space and giving it a handicap versus the generator (that’s my hand-wavy interpretation of it anyways).

Following one of the advices from the ganhacks repository, I also added some dropout to the discriminator layers. As far as I know, there is still some debate as for why does dropout improve the training of neural network. In the case of a GAN, my own intuition is that it introduces noise into the training, which prevents the generator/discriminator pair to get stuck in a local minimum where none of them would improve. Just like the solution to a problem may become obvious after going out and clearing your head for a while, perhaps dropout forces the discriminator to come up with new approach to the problem, by making it forget parts of what it already knows.

It took a few attempts to find a configuration where the training would not get stuck. Every time it got into a bad state where the one of the losses plummeted to zero, I had to stop the training and start over again after tweaking the knobs mentioned above. But interestingly, once I found a balance that worked for the first hundreds steps, the training never got stuck again and my two competing networks learned from each other nicely until the end, with no manual intervention required.

I let the training run for about half a day on my laptop, powered by a GTX1060 (it’s the 6GB model, thankfully. I doubt the GAN would have been able to fit in VRAM otherwise). I didn’t set a fixed limit on the number of iterations, and rather let it go on until I estimated that the models weren’t learning anymore.

But evaluating the training progress of a GAN is somewhat tricky. As I mentioned before, you cannot monitor the losses to check that the GAN is actually learning, so instead, my training code was set up to take a random sample from the generator every 10 steps. That way, I could see the random blobs of noise produced by the generator slowly turn into consistent shapes over iterations, as the generator learned more and more of the particularities of the input dataset - a quite fascinating process.

Here is a video showing the evolution of generator samples over the training :

What’s even more fascinating is that you can really see in which order the features were learned : first the generator figured out that the discriminator was always expecting a white background with “something” in the middle, so the first coherent samples only showed a black blob on a white background. But then it realized that the discriminator had learned to check for the presence of color (remember, I removed black and white pictures from the dataset), so subsequent samples showed those black blobs slowly morph into more diverse colors. Then the generator learned about the general shape of a mobile suit, and started shaping the blobs into pairs of legs. And finally, it learned about, arms, heads, and other protrusions that mobile suit designers like to add to their models (like shields, wings, backpack boosters, etc). Of course those details are hard to make out on a 128x128 image, but the generator learned to include them as best as it could nonetheless (although more as extrusions of the original shapes, rather than a new elements added on top).

The results

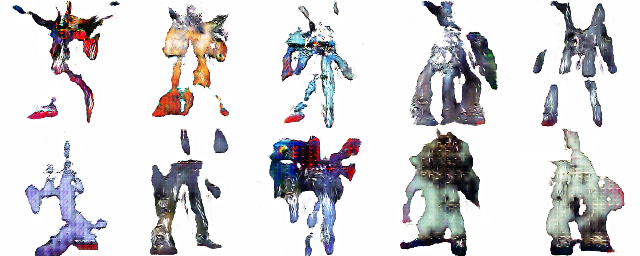

Overall, I’m extremely happy about the final results. For a first dive into GANs, I wasn’t expecting to get anything more than random colored blobs, and seeing the samples slowly morph into bipedal shapes completely blew my mind. Sure, the final images wouldn’t fool a human up close ; but if I mixed them with the original dataset, I bet you would have trouble telling some of them apart from a quick glance. And that’s exactly what a GANs is supposed to achieve.

Here are some of the best results :

And here are some of the worst :

The results are also surprisingly diverse. I was afraid the generator would get confused my the multitude of different shapes in the input dataset, and collapse into producing only amorphous blobs as a median ground. But nope ! In the generated samples, you can find anything from streamlined designs reminiscent of the Exia, to big, heavy mobile suits looking like a Dom, or convoluted designs with bits and pieces sticking out, similar to the Kshatriya. Unfortunately, smaller details like thrusters and fins are too hard to make out at that resolution, and end up looking like pixel smudges. But you can tell that the generator is trying its hardest to match the pixel color distribution in those smudges to the original images.

Speaking of colors, one thing that surprised me was how faithful the color schemes were in the final results. The generator didn’t simply mix random colors : it actually learned the most common schemes in the original dataset and what colors were supposed to go together. That’s how I ended up with generated mobile suits that were entirely green, purple or blue, following the visual style of some of the factions in the Gundam multiverse. A surprising number of images even boasted the iconic red-white-blue-gold scheme that traditionally marks the main protagonist’s machine in a Gundam show. Which is surprising given that those machines aren’t even that common in the input dataset. It’s possible that the generator learned that color scheme precisely because it’s so distinctive, or maybe I’m just biased in my evaluation because that scheme jumps out so much in the results.

However, even if the color schemes are mostly consistent, the generator has a really hard time at drawing a clear delimitation between surfaces with different colors. The colors often end up blending into each other, giving a “smudge” effect that’s closer to a water painting than an “anime” style. I’m only guessing here, but I suspect the very nature of the DCGAN architecture makes it incapable of reproducing the high-frequency parts of an image signal (like edges). DCGAN can get away with it when generating real-life photographs, because the images are generally complex enough for the smudges to be lost among other details. But when producing anime pictures, clear-cut surfaces of flat colors are expected in the results, and so that limitation becomes much more apparent.

Conclusion

That was a fun project ! It’s really a testament to the power of GANs that someone like me with zero experience and a measly laptop GPU is able to produce even remotely acceptable results. Now think of the resources that companies like Google, Facebook or Nvidia have at their disposal, and shudder…

I have a few ideas to try improving my GAN. First, the most obvious change is bumping the resolution up to 256x256. Small details are really hard to make out on 128x128, even on the original images. Doubling the resolution will certainly allow the GAN to produce finer details, and I believe it might even help its understanding of the original dataset, because specific shapes (like heads, thrusters, fins, etc) will become easier to identify. But increasing the resolution without blowing up the memory consumption is going to be a challenge. Adding another convolution/deconvolution stage will likely imply reducing complexity in other layers to stay within the memory budget.

Then after that, it would be nice to find a solution to the “smudging” problem I described earlier, because doing so would tremendously increase the quality of the generated image. I have no idea what’s the right way to proceed yet ; perhaps a constraint on the generator to force it to produce only flat colored surfaces, or maybe a complete architectural change…we’ll see. Exploring different architectures is definitely something else that I’d want to try.

Stay tuned !

The full code for this project is available on Github. The web scraping script is included but not the original dataset, since I do not own the rights to it.